3. HOW do we address Undernutrition?

Nutrition High impact interventions include the following:

1. Promotion of exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months

2. Promotion of complementary feeding after 6 months

3. Promotion of improved hygiene practices

4. Vitamin A supplementation

5. Zinc supplementation for diarrhea management

6. Deworming for children

7. Iron‐folic acid supplementation for pregnant women

8. Iron fortification of staple foods

9. Salt iodization

10. Multiple Micronutrient Supplementation for under 5s

11. Prevention or treatment of moderate acute malnutrition

12. Prevention of treatment of severe acute malnutrition

Community based Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM)

The Community Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM) model is an approach designed to provide early detection and treatment of acute malnutrition in the community as well as support high coverage of cases as quickly as possible. It was first designed by Valid International through research they did between 2001-2005, which concluded that the CMAM model was the best approach for treating children with SAM in an emergency context as an alternative to traditional inpatient care. WHO and UNICEF later endorsed the community-based care of children with SAM in 2007, and there are as guidelines for treatment of children with SAM. However, there are currently, no WHO guideline for the management of moderate wasting, although children with moderate wasting are treated with ready to use supplementary foods (RUSF).

CMAM has four main components

- Community mobilization and engagement

- Targeted supplementary feeding program for the treatment of Moderate Acute Malnutrition (MAM).

- Outpatient therapeutic feeding program (OTP) for the treatment of Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM).

- Inpatient treatment of SAM with

CMAM model is based on the principles of proving safe, effective therapeutic food for people to use at home; working with communities to help identify cases of malnutrition to encourage early detection; delivery of therapeutic food through existing structures reducing costs through integration of the treatment of malnutrition into health structures. The dramatic improvements in impact created by the CMAM model in combination with ready-to-use foods (RUFs) have led to a universal agreement that CMAM is now the preferred intervention approach for the treatment of malnutrition.

Determine the appropriate programme type/objective

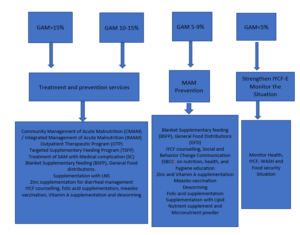

Depending on the context and the objective of a nutrition response there are four different end points or interventions:

- Prevention and Treatment: Global Acute Malnutrition (rates of 10-15%)

- Prevention alone (GAM =5-9%)

- Treatment alone (>15% GAM with limited resources)

- No additional intervention than strengthening IYCF-E and monitoring the situation (GAM= <5%)

The illustration shows you when to implement, in most emergencies combined nutrition treatment and prevention services are the right course to take (for more information refer to Annex 5.3).

Types of Nutrition programs and their Objectives

There are guidelines for selecting nutrition feeding programs to help identify the appropriate interventions, how to implement, monitor and evaluate their effectiveness. For more information on this please refer to Annex 5.7. The tables below will give you a brief overview of the main nutrition feeding programs during emergencies, their objectives, target population, when and how they are implemented.

|

Blanket Supplementary Feeding Program (BSFP) |

| Objective: The objective of the BSFP is to prevent acute malnutrition in young children aged 6-59 months and pregnant and lactating women in an emergency. It creates opportunities for community mobilization, community screening, referral for the management of SAM and MAM as well as for adding child survival interventions such as deworming, vitamin A supplementation, immunization and/or measles vaccination campaigns. |

| Target: Children aged 6-59 months and Pregnant women in their second trimester and lactating women with children aged 0-24 months with no malnutrition but at risk of developing it. |

| When: This is implemented when there is a high to serious level of acute malnutrition in the community (10-15% or above), coupled with high food insecurity, high prevalence of chronic malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies. It is typically implemented during the lean or hunger season where food availability and access is limited. |

| How: Provision of Medium Quantity Lipid Nutrient supplement (MQ-LNS) called Pumpy Doz that for children aged 6-59 months and Plumpy mum for PLW to be given as one sachet per day. Small quantity Lipid nutrient Supplement (SQ-LNS) called Nutributter is also used for children aged 6-23months and Enov Mum for mothers. For both children and pregnant and lactating women CBS+ or ++ (Corn soya blend) can also be provided together with oil. The deciding factor between choosing CSB++ and LNS is the household’s ability to cook which is essential for provision of improved fortified blended foods such as Super Cereal Plus. Therefore, in the absence of cooking facilities or easy access to fuel or potable water, only ready-to-use foods are recommended for nutrition interventions in emergency settings |

| Duration: BSFP is a seasonal program that is implemented between 3-6 months depending on the severity of the emergency; during the lean seasons where food insecurity is high and malnutrition rates peak. |

|

Targeted Supplementary Feeding Program (TSFP) |

| Objective: To treat moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) in children aged 6-59 months and Pregnant, lactating women; reduce mortality risk associated with MAM; and provide follow up for children with Severe acute malnutrition (SAM) |

| Target: Children aged 6-59 months and PLWs with moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) |

| When: In non-emergencies GAM of at least 10 % or GAM of 5–9 % but with aggravating factors (Poor IYCF practices, chronic food insecurity, high childhood morbidity and poor access to health and WASH services). In Emergencies its implemented when GAM is 10-15% or above. |

| How: Specialized nutritious foods and blended fortified food are provided on a regular basis (Either biweekly or monthly depending on the modality). Normally children are provided 1 sachet of Ready to Use Supplementary food (RUSF) every day and PLWs receive a fixed ration amount of fortified blended CSB+ and oil. |

| Duration: The program continues if there is high GAM or low rate of GAM with aggravating factors. However, children and women are normally in the program for a maximum of 4 months before they get discharged as either recovered cases or non-respondents. In the case of non-respondents, they are re-admitted into the program as a re-admission case, with close follow up. |

| Outpatient Therapeutic Feeding Program (OTP) |

| Objective: To treat Severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in children aged 6-59 months and Pregnant, lactating women; reduce mortality risk associated with SAM; and provide referral to who deteriorate from MAM |

| Target: Children aged 6-59 months with Severe acute malnutrition (SAM) |

| When: GAM of at least 10 % or GAM of 5–9 % but with aggravating factors (Poor IYCF practices, chronic food insecurity, high childhood morbidity and poor access to health and WASH services). |

| How: Through the provision of Specialized nutritious foods (Ready to Use Therapeutic food (RUTF) every day given on a weekly basis. |

| Duration: The program continues if there is high GAM or low rate of GAM with aggravating factors. However, children can be in the program for a maximum of 4 months before they get discharged as either recovered cases or non-respondents. |

|

Stabilization Center Support (SC) |

| Objective: To treat complicated severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in children aged 0-59 months to stabilize medical complications and appetite and provide referral back to OTP. |

| Target: Children aged 0-59 months with complicated severe acute malnutrition (SAM) |

| When: In non-emergencies GAM of at least 10 % or GAM of 5–9 % but with aggravating factors (Poor IYCF practices, chronic food insecurity, high childhood morbidity and poor access to health and WASH services). In Emergencies its implemented when GAM is 10-15% or above. |

| How: Through the provision of inpatient care and Specialized Formula milk given orally or intravenously every day given, in addition to medication. |

| Duration: The program continues if there is high GAM or low rate of GAM with aggravating factors. The stabilization center is only to stabilize children with medical complications with poor appetite and length of stay depends on the recovery of the child. Once medical complications are resolved, and appetite is regained, the child must be discharged to continue the rest of his/her treatment for SAM in the OTP in an outpatient setting. |

A good nutrition response should strengthen and create links between community and authorities in relation to mobilization, information sharing, and referrals. Very often programs forget to create links between community health workers, local authorities, and health center (HC) staff. It is very important that a clear and effective referral pathway is established between the different CMAM program components (OTP, TSFP, SC, IYCF). Community engagement in screening, nutrition promotions and IYCF counselling activities is paramount to the success of the nutrition program. Make sure you have specific activities on engaging local authorities and communities in program design, delivery, and feedback.

Determine the delivery mechanism: Several factors are important to consider when planning the delivery of a prevention of acute malnutrition programs, such as access to the population, scale of the emergency (including total area affected, etc.), implementation capacity and population density. For instance, population density is an important consideration when determining the number of treatment or delivery sites to ensure access to the sites as well as reducing the time spent to reach the site and for waiting at the site. In densely populated areas, it may be necessary to have multiple days a week for program delivery. They may be integrated with other distribution platforms or other services depending on the situation.

Articulate well the exit strategy: If the program plans to hire specific staff to support the Ministry of Health (MOH) staff to deal with heavy caseload, ensure you have an exit strategy, hand over plan and capacity-building activities right from the beginning of the program and include the associated cost for handing over of the services. Activities should be decentralized as much as possible with a lot of community engagement, this way the chances of activities continuing past project period is likely with the support of local authorities and MOH.

Ensure continuum of care: SAM treatment should be followed by a period of continued support, through MAM treatment programming. Planning of SAM and MAM treatment should be done in a way that promotes a continuum of care for acute malnutrition. Ideally sites should be co-located or as close as possible to each other, with 30 min of walk. When planning a CMAM program ensure you are planning to address both SAM and MAM as it is more difficult to coordinate with other agencies in an emergency context and to avoid the risk of children falling between cracks. It is also important to map whether stabilization center support is available in area where there is SAM and MAM programs, to ensure children with complicated SAM are effectively referred to stabilization centers (SC) in the hospitals as they require inpatient care. If the SC is non-functional, then consider supporting it to make the referral more effective. This can be done through the provision of food for caregivers and children, cooking facilities, nutrition supplies, capacity building of staff and transportation costs or vehicles.

Strengthen the prevention of Malnutrition: Make sure your program also includes activities for the prevention of acute malnutrition such as Social and Behavior Change Communication (SBCC) on infant and young child feeding practices, nutrition, health, hygiene education, micronutrient supplementation, deworming, Vitamin A supplementation, measles vaccination, and provision of Lipid based nutrient supplements. Link with other services addressing immediate and underlying causes of malnutrition (Liaise with CARE WASH, Health, Food Security teams to co-locate services to maximize the impact of the response.)

Ensure effectiveness of the Nutrition programs by:

- Delivering services at scale (broad geographical area)

- Delivering high impact interventions in highly vulnerable areas**

- Providing frequent meaningful interpersonal contacts with mothers, caregivers, and family members.

- Use all forms of Social and Behavior Change Communication (SBCC) for IYCF messaging and use consistent and harmonized messages through Interpersonal communication, social mobilization, and mass media.

- Address both nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive determinants of malnutrition.

- Be data driven, include measures of quality, process, outputs, and outcome.

- Continued monitoring of high-level indicators generally collected through the Demographic and Health Surveys or large-scale population-based surveys (SMART, SQUEC, IYCF) Increase impact and cost‐effectiveness by better integration across multiple sectors.

- Ensure integration of disaster and emergency preparedness into the program cycle in order to respond effectively, quickly and protect the nutritional status of the population, particularly the most vulnerable.

- Provide capacity-building and essential supplies for health workers for screening of malnourished children and treatment of moderate and severe cases at health facilities.

- Integrate nutrition treatment programs into existing health infrastructure and provide integrated services.

Nutrition-Sensitive Programming

Apart from direct nutrition interventions to tackle malnutrition, there is also growing recognition that nutrition sensitive programming can reduce the impact of malnutrition and strengthen resilience in the long term. The evidence of the use of Cash and Voucher assistance (CVA) for nutrition outcomes is growing and it has shown that CVA can improve nutritional outcomes by impacting on the underlying determinants of adequate nutrition This can occur through three main pathways:

- Access to CVA can improve access to food, health, water, medication, and transportation to feeding centers.

- Cash recipients receive social, and behavior change communication (SBCC) on optimal infant and child feeding and the importance of a balanced diet, which can in turn improve their household dietary diversity.

- Empowering women in their access and control over dietary decisions can facilitate better and informed decisions over what they want to eat without thinking of the economic pressures. Furthermore, the increase in household income associated with CVA can in turn increase the time available for practicing important infant and young child feeding practices such as exclusive breastfeeding, appropriate complementary feeding, and continuation of breastfeeding up to 2 years.

By using the conceptual framework of malnutrition, we can understand how CVA can be used to improve nutritional outcomes. The below table helps you to understand the different barriers at each of the underlying determinants to adequate nutrition and highlights how CVA can be used to address these gaps or barriers. It highlights common barriers on the demand and supply side with those in yellow considered ‘economic barriers’ and can be addressed by enhancing additional purchasing power, e.g., CVA. Economic barriers are all on the demand side. They include both financial barriers related to the lack of financial resources at the household level to access goods and services as well as opportunity costs. This can guide you to identify which gaps/barriers (demand or supply) your project will be addressing and how to use CVA for it. Therefore, it’s important to understand these gaps in initial need assessment to determine and justify the need for CVA for improving nutrition outcomes in your respective programming (for more information refer to Annex 5.8).

Tips for writing Emergency Nutrition proposals

In order to write a successful nutrition proposal, you need to document a strong needs analysis and the prevalence of GAM in the affected area should always be referenced as it’s a key indicator of vulnerability. For the decision-making purposes a GAM prevalence (wasting) is generally considered critical when prevalence is above 15%, serious when between 10 -15% and low when it is < 5-9 % and acceptable when it’s <5%, however these WHO thresholds have recently been revised (see classifying malnutrition section). Understanding the seasonality of GAM in the emergency affected population is also critical in classifying the GAM prevalence. If there is a lack of data on GAM prevalence or a recent SMART survey done in the area (within the last 3-6 months), then you can do the following:

- Review outdated GAM prevalence alongside contributing factors during that same period and make assumption about whether the situation is still the same or much worse.

- Review recent data on contributing factors (e.g., infant, and young child feeding practices, dietary intake, morbidity, access to health and WASH services, household food security, feeding and care practices, poverty etc.) and assess whether similar trends from the outdated GAM may still apply.

- Review performance data from programs and routine systems (i.e., CMAM data, IYCF counselling and sessions, screening data, growth monitoring, immunization, micronutrient supplementation, social protection, etc.) and compare to previous years to identify any changes in trends of changes on nutrition outcome data other than seasonal changes.

GAM prevalence can also be corroborated by the number of children with MAM and SAM in treatment if we have a clear understanding of the coverage and therefore the current met need. When there is no recent SMART data, screening data or program admission data then as a final call for the decision-making process information on risk of deterioration may be used.

How do you evaluate the risk of Deterioration in an area?

Since wasting is an outcome of poor health or care and inadequate dietary intake, childhood morbidity and food insecurity information on these factors in the need assessments or situational analysis of a proposal can help infer the risk of wasting amongst a population.

- Increased childhood morbidity: Increase in incidence of diarrhea, acute respiratory infection, malaria, and measles in non-immune populations are common childhood in emergencies. Certain types of emergencies (flooding, earthquake) and settings (urban, IDPs camps) are more likely to cause an increased risk of morbidity. The population’s access to water (quantity and quality), sanitation and hygiene services and crowding is also an important component in determining morbidity risks. Thus, collecting information of vaccination coverage, supplementation including Vitamin A, and common childhood morbidity in an area can help infer the risk of wasting amongst children under 5.

- Decreased food security (disrupted food availability, access, or utilization): Conflicts, drought, flooding and earthquakes have major impact on food security especially on the availability and access to food. During emergencies markets are often disrupted, damaged and there is a loss of livelihood negatively impacting on household income. Increased food prices also have a significant impact on the prevalence of acute malnutrition in an area. Hence you should collect available data on household food security, consumption and market information and household coping strategies. Negative coping strategies such as skipping meals or reducing intake will have direct impact on GAM. The likely deterioration of the food security situation in an area, including the proportion of households that are likely to be moderately or severely food insecure, should also be highlighted in the light of the increasing incidence of malnutrition.

- Infant and young child feeding practices in Emergencies (IYCF-E): Infant and young child feeding practices are often negatively affected during emergencies, and this can result in an increase in malnutrition in young children. Babies 6-23 months are the most affected since this is when complementary foods are introduced, and children’s diets begin to diversify to meet their growth requirements. Emergencies can set back this important milestone if diets are inadequate and available food is unsanitary or unsafe, exposing children to pathogens that cause illness. Mothers may be affected by multiple stresses and unable to breastfeed sufficiently or care for their infants optimally. Therefore, it is important to address IYCF-E as part of the prevention of acute malnutrition and treatment of SAM and MAM interventions, particularly to emphasize exclusive and continued breastfeeding and optimal complementary feeding in children 6-23 months of age. Therefore, try to include the prevalence rates of these different indicators either from a recent IYCF KAP survey conducted in the area or use the data captured from national demographic surveys in order to better assess the risk of malnutrition in the area. In an emergency stress, lack of food, limited privacy, and uncontrolled distribution of breast milk substitutes (BMS) are among the challenges that can undermine infant feeding practices. Because the interruption of breastfeeding can lead to the rapid deterioration of an infant’s health and lead to malnutrition, it is important that there is professional support and counselling at different contact points within the nutrition program.

- Significant population displacement: Population displacement is another which may influence malnutrition as people lose their livelihoods and their income. As a rule of thumb if the displacement is increasing consider the risk of malnutrition to be high (due to limited basic services, overcrowding, unhygienic conditions etc); and if there is no displacement or no increase in displacement or the population are sparsely spread consider the risk to be low.

- Population density can also influence the risk of illness/disease outbreak especially in overcrowded places. In addition to this there are also circumstances where despite a low prevalence of GAM there will be many children in need of services due to the high population density; thus, leading to high caseload. Therefore, despite the low GAM prevalence information of number of expected cases in an area is also an important determinant for the need of an intervention and choosing service delivery.

For further guidance and tips on writing BHA specific nutrition concept notes and proposals see Annex 5.9 and 5.10.