Phase 5: Reflecting, Learning and Influencing

To efficiently advocate for localisation, we need to demonstrate the effectiveness of our partnerships and relationships with local partners. It does not just promote and enhance localisation but strengthens organisational capacities of CARE and our partners. Setting partnership output/outcomes will help improve our humanitarian action and achieve our program objectives.

Assessing partnership quality and effectiveness

A great humanitarian partnership is only possible if all parties collaborate equitably with each other, specifically in a crisis setting where things change quickly.

There are cases when CARE or the partner has limited knowledge or capacity to implement best practices for activities like distribution, and a weak grasp of issues like SPHERE standards, accountability mechanisms and gender sensitive programming. Therefore, it is important to assess the quality and effectiveness of partnership so both CARE and partners can learn from the experience and be able to address identified challenges or replicate best practices.

Learning questions to assess partnership quality and effectiveness

On Results and Impact

- What results does the partnership produce? Are there clear and measurable partnership output/outcomes?

- Do CARE and partners achieve their shared goals (joint project) and organisational goals?

- How does the partnership add value to each organisation?

- Does the partnership achieve wider impact and influence?

On Functions and Efficiency

- Are there strong and appropriate communications and accountability mechanisms in place?

- Are there enabling internal processes and systems of CARE and partners for partnering? Are there flexible processes/systems and light bureaucracy for partner compliance?

- Do CARE and partners maximise the strengths and expertise of each other during the partnership?

- Are the roles and responsibilities of each other clear? Are they outlined in some forms of agreement such as MOUs?

- Are there regular reviews to assess the quality of partnerships and address emerging issues and concerns?

On Collaboration

- How does the partnership promote collaborative approach?

- How are partners provided opportunities to speak up and advocate at the discussion and decision-making tables?

- Does the partnership present joint branding and visibility?

- Are individual expertise and preferred ways of working incorporated consciously and constructively in your partnerships or response strategy?

- How do you allot time and resources to strengthen capacities of each other and to building/maintaining the partnership?

- Does the partnership display willingness of all parties to share risks or take measured risk for the benefit of the partnership?

Tips to strengthen the partnership and ensure program quality

- Foster common understanding on a program by holding an inception meeting for CARE and partner staff to discuss standards, the objectives, activities, obstacles, program management, etc.

- Run training sessions for partner staff at the earliest possible time. Ensure that they are relevant, concise, and well targeted, and try to conduct them where program activities are being implemented.

- Provide tools and materials to support training. Preparing translated manuals prior to an emergency is a good practice.

- Follow up on training with physical visits, meetings, or refresher courses. This will be much more effective than just one-off events.

- Consider seconding CARE staff to partners to mentor them for a defined period or arrange for partner staff to learn more about our operations.

- Ensure that program monitoring covers quality and standards issues.

- Budget for partner capacity strengthening interventions in project proposals.

- Give partners access to tools and materials such as the CARE Emergency Toolkit, the Gender Marker, etc.

[REPORT] CARE Lebanon Partnership Workshop (2020)

[REPORT] Localisation in Practice: A Pacific Case Study (2016)

Strengthening evidence-based Documentation and Learning

CARE should continuously strive to be a learning organisation, demonstrating openness and transparency by sharing our best knowledge and methods and constantly seeking to learn from others.

CARE has access to a wealth of expertise, good practices, and innovation from within the CARE family and from our networks and partners. Our role should consist in collecting, documenting, and sharing approaches, and adapting and contextualising knowledge and well-tested models to make them useful to local partners and thereby scale up gender-responsive approaches.

Tips to strengthen documentation and learning with partners

- Jointly develop a documentation and learning plan with partners.

- Identify information and existing models that can be adopted to avoid duplication of resources.

- Allot budget for documentation and learning activities.

- Set up a simple yet efficient information/knowledge management system with partners.

- Invest in equipment for documentation like digital cameras and audio recorders.

- Conduct monthly or quarterly learning reviews and knowledge exchange with partners – can be done physically or virtually.

- Organise activities that bring together civil society actors, researchers, INGOs, multilateral organisations, donors, government officials and other relevant stakeholders on specific agendas. Create an opportunity for all to learn from each other and together.

- Synthesise findings from monitoring visits and share with the entire team.

- Develop learning materials such as human-interest stories, case studies, brochures etc.

Shifts in Power Dynamics and Leadership

The shifting of power relations in favor of formerly excluded groups (including women) can evoke resistance of those in power and lead to backlash against these groups. To avoid doing harm, CARE should expand and strengthen spaces for dialogue and negotiation, in order to channel demands and negotiate competing interests between actors within civil society, or between civil society, state actors (including political parties) and private sector.

In fragile contexts, characterised by mistrust at all levels and between civil society and the state, CARE should play a role in improving trust and re-building social contracts within civil society and between CSOs and the state through dialogue and accountability mechanisms aimed at improving governance and service delivery.

As an international non-partisan organisation, CARE should sometimes play a mediator role, and help parties to identify solutions that will enable them to move forward. This role can also involve training local conflict mediators and supporting mediator organisations.

CARE is privileged to have access to millions of women and to a range of women’s organisations and networks who play such conflict mediator roles on a daily basis, and from whom we have much to learn. As part of the context analysis and do-no-harm approach, CARE can partner with and train local actors in conflict mapping and gender analysis tools to map relations among stakeholders, both between civil society organisations and between civil society and other stakeholders.

Fit-for-partnering Review Guidelines

A Rapid Accountability Review (RAR) is a rapid performance assessment of emergency response against CARE’s HAF that takes place within the first few months of an emergency response. It generates findings and recommendations that are used to make immediate adjustments to the response. It is also a key source for any response review and performance management process. It usually entails interviews with CARE management, staff, communities and other key external stakeholders, and is led by an independent team leader. The overall goal of the RAR is to improve the quality of CARE’s response by assessing its compliance with established good practice.

A Real-Time Review (RTR) is a rapid internal assessment carried out by CARE staff in order to gauge relevance, efficiency, scale and basic quality of the response or adaptation. It serves to adjust or correct the manner in which the response is being carried out. RTR requires an open discussion and team-based analysis of the response performance so far against global performance standards and Indicators as well as against response specific targets and commitments.

An After-Action Review (AAR) is an internal performance review and lessons learned exercise that takes place within the first 3-4 months of a crisis response. It usually takes a workshop format and brings together key staff who have been involved in the response from the country program, CARE Lead Member and other parts of CARE. These learning activities are independently facilitated.

How to engage partners in RAR/RTR/AAR

- Ensure partners are included in the participants of a RAR/RTR/AAR. An independent facilitator is usually appointed to help create an open and unbiased environment.

- The location and method for conducting the review should also be convenient for local partners so they can provide their full attention.

- The review’s objectives and scope are developed with all the participants including the partners.

- Diversify the level of participation of partners. It is important to include the partner’s senior management team, but it would also be helpful to get insights from other partner staff (program, finance, subgrants and MEAL).

- Develop a growth/learning mindset or tone for the review. Sometimes CARE or the partners may feel that they have been committing mistakes in the partnerships and that might affect the relationship with each other. The learning mindset from both parties will help us move towards improvement.

- The results of the review should also be shared and presented to the partners so they can also provide feedback or learn from the findings.

[GUIDANCE] Rapid Accountability Review (RAR) (2017)

[TOOL] Real Time Review (RTR) guidance for planning & facilitation – COVID adaptation (2020)

[SAMPLE] CARE Nepal RTR Plan (2020)

Advocating with and for Local Partners

CARE should continue to enter alliances and join networks to amplify voice on key issues. To be a good networker, we need to continuously update our mapping of local actors in a given context and be good at forming relevant alliances. At times, we should cede space for partners to raise their own voices where possible and when desired by the partner.

In collaboration with other civil society actors, women-led and women’s rights organisations, individual advocates, we can draw on our global network that include peer INGOs, research institutions and other CSOs at all levels. Partners are often expecting us to facilitate access to our networks within and across regions.

Brokering healthy partnerships and win-win scenarios is a role that requires specific skills such as meeting facilitation, interest-based negotiations, coaching and partnership review, which need to be enhanced for CARE to play this role. Focusing on partnership management – and not only on partner management – requires new skills, tools and mindsets.

As outlined in the Humanitarian Impact Area Strategy, CARE and partners will significantly scale-up and deliberately link advocacy efforts on three distinct but mutually reinforcing advocacy streams:

- Women’s meaningful and direct participation in humanitarian, conflict, peace and recovery coordination and decision-making bodies at all levels. This includes women’s individual and collective participation through scaling-up tested models, and work to address barriers to their participation as well as CARE ceding space.

- Gender-transformative localisation and equitable humanitarian partnerships. This will help create enabling conditions for women’s direct and meaningful participation and implies advocacy for a redistribution of power towards local actors, prioritising women’s organisations, calling for recognition of their role, expertise, and legitimacy and for substantial quality funding to enable them to lead humanitarian efforts, deliver on their mission and invest in their longer-term institutional development.

- Leverage our dual mandate, multi-sector approach, and presence in Fragile and Conflict Affected (FCA) settings to add our voice to advocacy on operationalisation of the Triple Nexus as a fundamental approach to bridge the growing gap between humanitarian needs and funding. This will include calling for:

- expanding the financing base, including asking development donors to contribute to collective outcomes to prevent and recover from crisis, while asking all donors to finance durable solutions for protracted crisis, conflict and forced displacement situations; and

- greater agility and efficiency through continued advocacy on harmonisation and simplification of donor and UN agencies’ funding mechanisms and processes.

Advocating with donors for local partner support

CARE should use its leverage as an INGO and member of sector/NGO coordination groups to monitor national NGO legislation and advocate locally, regionally and globally for enabling legislation and for the inclusion of local civil society as actors in development in policy design, budget monitoring, etc.

In many cases, CARE chooses to support existing local and regional coalitions to engage with governments and political parties or lobby donors to negotiate the opening or preservation of existing space. In other cases where such platforms do not exist, CARE should support their creation on an inclusive basis.

CARE can use its connections with authorities and political parties to make them more open to receiving recommendations from civil society. In countries where local authorities do not listen to INGOs, CARE can ally with other local and regional actors (e.g. trade unions, state-related workers’ associations, regional state conferences) to include local actor’s perspectives.

In relation to donors, CARE should lobby to make flexible funds available for long-term institutional support to local organisations (especially for women’s rights organisations that are generally underfinanced); design gender-sensitive results-based management systems and get donors to share financial risks. We should also lobby to improve access to funding for grassroots and informal groups.

For example, a flexible country-based pooled fund model that can support expenses for partnership development and capacity strengthening, and the inclusion of local partnerships as criteria for project proposal selection can also support our localization commitments.

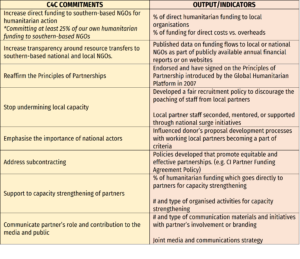

Assessing and reporting localisation commitments

When developing our humanitarian partnership strategy, it is important to look at our existing localization commitments with the Charter for Change and the Grand Bargain (see here for the list of commitments) and integrate these into our overall strategy. There are cases that not all commitments are included in the strategy. It will all depend on the context and your capacity to realistically meet all those commitments.

Practices to integrate localisation in joint humanitarian response

- Maximise and utilise local and national human resources and capacities unless specific expertise is lacking. Identify national or local priorities and let them drive the response, with international support aligning to these priorities.

- Provide funding to local actors as directly as possible. The funding should be tracked in a transparent manner, cover direct and some overhead/admin costs.

- Provide a leadership role to partners at local/national level – with international taking a support, complementary role.

- Build and strengthen local and traditional practices, not replace them. Also, build upon or strengthen local partners’ systems and ways of working rather than undermining.

- Identify gaps within the local organisation and address those during preparedness and response.

- Recognise local partners’ contributions to the response and give them visibility in the media, with the public and donors.

- Encourage joint participation and ownership throughout the response; should be reflected in partnership agreement and in joint review/learning events.

- Promote the engagement and leadership of partners in local/national humanitarian coordination process.

- Implement efficient and harmonised reporting to donors.

Sample questions to assess localisation

- Is the local partner better positioned as a first responder for future emergencies (enhanced capacity – scale/scope, enhanced visibility/reputation, influence)? Where does CARE fit in this scenario?

- [Q to local partner] What have you learned from this response that puts you in a better position?

- Is the local partner in a better position to attract humanitarian funding in the future, especially direct funding? How does CARE add value or contribute to this?

- Has the visibility and reputation of the local partner been enhanced as a result of the response? How do we contribute to this?

- Is the local partner more aware of its gaps/weaknesses in humanitarian action and actively addressing these (training, capacity strengthening etc.)? If yes, how does CARE support the partner?

- Is the local partner more engaged and effective in humanitarian policy debate at all levels? Are international partners supporting participation and influence of local partners in policy debates beyond their country? If yes, how does CARE support the partner to achieve this?

Some indicators to measure and report our Charter for Change localisation commitments

[REPORT] Localization in Operational Practice: CARE’s experience in Sulawesi and beyond (2020)

[SAMPLE] CARE Nepal Reflections on Humanitarian Partnership and Localization in COVID-19 (2020)