3. Gender in Localisation

CARE is deliberate about partnering with local NGOs committed to gender equality in delivering a humanitarian response, and we also strive to work more, and more meaningfully, with women’s rights organisations in emergencies. This is key to how we “hardwire” gender in our humanitarian partnership work.

more meaningfully, with women’s rights organisations in emergencies. This is key to how we “hardwire” gender in our humanitarian partnership work.

The impact of crises on people’s lives, experiences and material conditions differ based on their gender and sexuality. Gender intersects with other forms of diversity which can exacerbate unequal power relations e.g. characteristics such as race, caste, ethnicity, sexual orientation and disability.

Our humanitarian mandate is to meet the immediate needs of women, men, girls and boys affected by natural disasters and humanitarian conflicts in a way that also addresses the underlying causes of people’s vulnerability, especially as a result and cause of gender inequality.

Our activities during a humanitarian response can increase and reinforce, or reduce, existing inequalities. Integrating gender into every stage of a response is therefore a core part of achieving our humanitarian mandate, even and especially when we are working with local NGO partners that do not necessarily specialise in gender.

Who can “do” gender in emergencies? All CARE staff and partner staff should use the four steps in the GIE Approach to advance gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls through humanitarian action.

A key reminder is that we must link our and our partners’ humanitarian programming to CARE’s existing gender equality development programming before, during, and after a humanitarian crisis.

Gender in Brief

Rapid Gender Analysis (RGA)

Women Lead in Emergencies (WLIE)

Gender-Based Violence in Emergencies (GBViE)

Partnering with Women-Led Organizations (WLOs) and Women’s Rights Organizations (WROs)

AMEND CONTENTIntroduction – Why Partner with Women-Led Organizations (WLOs)

Women, men, boys, and girls are affected differently during humanitarian crises as a result of underlying gender inequality and power imbalances. As an organization focused on gender equality, CARE recognizes and seeks to address the specific needs of women and girls during humanitarian crises.[1] WLOs are critical actors in this effort. WLOs are on the frontline of humanitarian response, living in, and working with and for, their communities. They are best placed to understand the needs of women and girls because they already have an operational presence at the community-level, before the onset of crisis.[2] Not only do WLO responses best identify and respond to community needs, but they also ensure sustainable, long-term change. CARE WLO partner, Fundación Alas de Colibrí, outlines: “Arriving in a place and asking questions is not enough to create a community. The work [WLOs] do with the community is work that takes a long time. Many of the people who come here do a project and then think that they are finished; there’s a lack of continuity and sustainability.”[3] At CARE: “Our humanitarian mandate is to meet the immediate needs of women, men, girls and boys affected by natural disasters and humanitarian conflicts in a way that also addresses [emphasis added] the underlying causes of people’s vulnerability, especially as a result and cause of gender inequality.”[4] Partnering with WLOs is a critical way to ensure that humanitarian interventions meet the needs of women and girls and create long-lasting change.

Defining Women-Led Organizations (WLOs) and Women’s Rights Organizations (WROs)

Across diverse humanitarian contexts, CARE works with both WLOs and WROs to advance women’s rights, and women’s voice and leadership, in humanitarian preparedness and response. While both types of organization have a role to play in humanitarian action, it is important to note the difference in women’s direct participation and engagement in the leadership structure of these organizations.

CARE’s definition of a WLO is closely aligned with the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) definition:

“Any non-governmental, not-for-profit and non-partisan organization that is (1) governed or directed by women; or (2) whose leadership is principally made up of women, demonstrated by 50 per cent or more occupying senior leadership positions, and (3) focuses on women and girls as a primary target of programming.[5]

Women are central to the leadership of WLOs. CARE seeks to work with these organizations in line with its focus on gender equality and the programming principle of working with partners, “deepening its existing approach to [equitable] partnerships for sustainable development and humanitarian assistance with an emphasis on amplifying local women leaders and movements.”[6] CARE has also made several external commitments to advancing humanitarian partnership and localization, endorsing the Principles of Partnership, the Pledge for Change, the Charter for Change, and the Grand Bargain.[7]

CARE and the IASC define a WRO as an:

“(1) Organization that self-identifies as a women’s rights organization with the primary focus of advancing gender equality, women’s empowerment and human rights; or (2) Organization that has, as part of its mission statement, the advancement of women’s and girls’ interests and rights (or where “women,” “girls,” “gender” or local language equivalents are prominent in their mission statement); or (3) Organization that has, as part of its mission statement or objectives, to challenge and transform gender inequalities (unjust rules), unequal power relations and promoting positive social norms.”[8]

The decision to partner with either WLOs or WROs is context-specific, dependent on the partnering organizations’ mission and vision alignment, and the objectives of the particular program. CARE seeks to work with both types of organizations to best meet the needs of women and girls in diverse humanitarian crises.

Centrality of Partnering with Women-Led Organizations (WLOs)

CARE has set a goal of: “10% of people affected by major crises receive quality, gender-responsive humanitarian assistance and protection which is locally-led.” [9] In order to meet this goal, CARE should partner with diverse WLOs:

“Decolonized humanitarian action and equitable partnership are central to CARE’s efforts to address power imbalances in our own organization and the wider humanitarian sector. We will embrace feminist principles and promote and support feminist leadership inside CARE and in the wider humanitarian community. We will work with youth-led/women-led/women’s rights organizations, and those working to address inequality and injustice, respecting humanitarian principles.”[10]

CARE’s Work with Women-Led Organizations (WLOs)

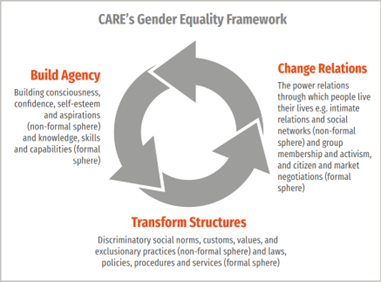

CARE’s work with WLOs is grounded in the Gender Equality Framework[11]:

In partnering with WLOs, CARE is building their agency, supporting a change in power relations between WLOs and decision-makers, and transforming the humanitarian structures in which WLOs operate. “Partnership in CARE” outlines CARE’s goal to increasingly transform into a “convenor, a connector and supporter of civil-society.”[12] Support to WLOs furthers this goal, ensuring that CARE is enabling WLOs’ direct work with communities, as well as their advocacy with governments and decision-makers.

Core Feminist Principles for Partnership with Women-Led Organizations (WLOs)

CARE-WLO partnerships are grounded in the following feminist principles:

- Through these partnerships, CARE decolonizes its traditional relationships with WLOs, ceding space and sharing capacity and power.

EXAMPLE – If CARE is offered a seat on a conference panel, as an international NGO, request that this invite be transferred to a WLO partner.

- The physical and emotional safety of all parties to the partnership is paramount, ensuring that all are safe to do their work.

EXAMPLE – If CARE does not send staff to a particular region, WLO partners should not be expected to travel to this region.

- Dedicated space is created to reflect on the partnership, lean into difficult conversations, and encourage mutual feedback.

EXAMPLE – Hold quarterly feedback discussions, asking WLO partners to come prepared with suggestions about how CARE can improve its partnership practices.

- Interactions between parties to the partnership are trust-based, respectful, and grounded in equality, recognizing the immense demands on women’s time and avoiding burdensome requests that are not of value to WLO partners.

EXAMPLE – If CARE is planning a global advocacy engagement with WLO partners, co-create the agenda to ensure that all meetings equally advance CARE and the WLO partner’s goals. If possible, CARE should remunerate WLO partners for their participation in these engagements (beyond covering costs and issuing per diem).

- Partnerships are co-created and iterative, continually learning from experience and onboarding feedback from all parties to the partnership.

EXAMPLE – CARE programming staff take note of partner difficulties in meeting compliance requirements and seek to adjust procedures, so they do not cause undue burdens on WLO partners.

- Parties to the partnership seek to evolve, improve, and grow the partnership in a mutually beneficial

EXAMPLE – Do not make requests from a WLO partner if the request merely serves to benefit CARE’s work and not the work of the partner organization– think about the incentives for WLO partners to engage with CARE and prioritize these equally with what incentivizes an INGO.

Equitable Partnership

CARE has committed to the Global Humanitarian Platform’s Principles of Partnership: Equality, Transparency, Result-oriented approach, Responsibility, and Complementarity[13] (please find a complete list of CARE’s external commitments on partnership in the “Our Commitments to Humanitarian Partnership and Localization” section). CARE seeks to imbue WLO partnerships with these five principles through an Equitable Partnership Approach. This approach seeks to transition away from a model in which WLOs were viewed as implementing partners, breaking down traditional program hierarchies to foster equitable partnerships between CARE and WLOs. As such, CARE establishes flexible, multiyear partnerships with WLOs, engaging them in all steps of the program life cycle, from conception. CARE also ensures that WLOs are involved in strategic decision-making regarding joint programs, and more broadly, on shared objectives. Through these relationships, WLOs are supported to have direct access to donors, humanitarian funding and humanitarian coordination mechanisms, and to access global advocacy opportunities beyond the scope of an individual program.

To ensure equitable partnership in CARE’s work with WLOs, this programmatic partnership strategy includes the following elements:

- Long-term relationships: Establishing partnerships outside of the program cycle, building long-term, trust-based relationships, grounded in shared values and objectives.

- Broad support: Collaborating with partners outside of specific programs, facilitating spaces for capacity sharing between CARE and WLO partners, and between different WLO partners (for example, through trainings, consortia, and peer-to-peer learning exchanges).

- Inclusion across the program cycle: Engaging partners in all steps of the program cycle, ensuring that they are part of program design, implementation, monitoring, adaptation, and evaluation.

- Flexibility: Ensuring that partners have flexible budgets and avoiding a hierarchy in project implementation by burden-sharing with partners when faced with obstacles, seeking innovative and effective solutions.

- Mutual donor access: Supporting partners to directly access donors and funding, and advocating with donors to increase these connections as well as their provision of quality funding, that is tailored to the needs and long-term viability of WLOs.

- Consistent and open communication and engagement: Keeping communication channels open for feedback from partners, remaining adaptable and available to partner needs, and meaningfully onboarding any feedback received.

- Language justice: Ensuring that all project communications and documents are available in partners’ native language.

- Ceding space: Prioritizing partner voices over CARE’s when provided opportunities to elevate partner profiles (recognizing the privileged position of international NGOs in high-level spaces compared to WLOs).

- Going the extra mile: Partners have many competing demands and by taking extra lengths to ensure their comfort, partners feel better prepared to engage in national, regional, and global activities, and high-level meetings.

- Adapting procedures to meet exceptional needs.

- Supporting partners beyond the scope of project work.

- Providing needed support for advocacy engagements, including technical, logistic, and administrative support.

This approach is not designed to be static, but should be iterative, evolving with and responding to WLO partner needs. It is characterized by:

- Continual re-evaluation of partnership modalities (through annual reviews, regular feedback sessions, an open-door policy so issues can be raised as they arise etc.)

- Participatory, feminist methods for learning and adaptation

- Ensuring that WLOs’ voices lead conversations

- Using learning for advocacy and transformational change

- Applying inclusive approaches that create space for women in all their diversity to become partners and tackle intersectional inequality

- Production of joint learning products in partnership with WLOs, regarding INGO partnerships with WLOs

- Self-interrogation

Practical Tools to Create and Implement Equitable Partnerships with Women-Led Organizations (WLOs)

Learning from Partnering with Women-Led Organizations (WLOs)

[1] https://www.careemergencytoolkit.org/gender/gender-in-emergencies/

[2] https://www.care.org/news-and-stories/resources/integrating-local-knowledge-in-humanitarian-and-development-programming-perspectives-of-global-women-leaders/

[3] https://www.care.org/news-and-stories/resources/integrating-local-knowledge-in-humanitarian-and-development-programming-perspectives-of-global-women-leaders/

[4] https://www.careemergencytoolkit.org/partnership/3-gender-in-localisation/

[5] On September 9th, 2024, CARE decided to adopt this definition with internal consensus.

[6] https://www.care-international.org/files/files/Vision_2030.pdf

[7] https://www.careemergencytoolkit.org/partnership/1-our-commitments-to-humanitarian-partnership-and-localisation/

[8] https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/iasc-reference-group-gender-and-humanitarian-action/iasc-policy-gender-equality-and-empowerment-women-and-girls-humanitarian-action-updated

[9] For CARE Staff, please refer to the Humanitarian Impact Area Strategy.

[11] https://www.care.org/news-and-stories/resources/cares-gender-equality-framework/

[12] https://www.care-international.org/sites/default/files/2022-12/PARTNERSHIP-IN-CARE.pdf

[13] https://www.unhcr.org/media/principles-partnership