2. The Humanitarian Partnership Cycle

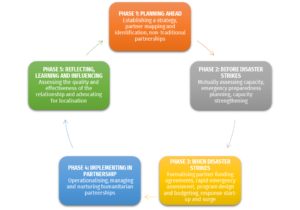

The Partnership Cycle summarises our understanding of the different stages in the life of a partnership. Partnerships are constantly evolving based on CARE’s and partners’ emerging priorities. Several types of partnerships may not conform precisely to this sequence, but many have used it as a framework for their partnership work in a humanitarian setting.

Working in partnerships can be divided into five different phases.[1] The process flow below shows the phases in the partnership process for a single project during a rapid onset emergency. However, a team may have strategic partners for a longer period beyond the duration of a project.

Ideally, the partnership process begins during the preparedness planning. The selection process of local partners and relationship building have been started or completed during “peace time” resulting in a contingency agreement jointly developed with the partners. Identifying and engaging your local partners during preparedness planning will save you considerable time and effort once an emergency hits.

Each phase in the process has critical steps to perform. The exact steps in the partnership process may vary in each response, depending on the context (e.g. your country program and partners’ resources and capacities). The reality of an emergency is often complex; hence the below guidelines should be tailored to your specific needs and context.

Note: This section presents the different phases and their minimum standards that require involvement of local partners. It is important to actively engage your local partners in each phase to achieve better results.

[1] When CARE provides funding to a partner, the “Partner Funding Agreement Life Cycle” in the CI Partner Agreement Funding Policy details 4 phases during the Life Cycle of the specific funding relationship: Pre-Award (includes selection); Contracting; Implementation and Monitoring; and Close-out.

Establishing a Humanitarian Partnership Strategy

A humanitarian partnership strategy allows the country program to identify key objectives and corresponding actions to develop and nurture partnerships with local humanitarian actors. It also supports the country program in achieving its humanitarian goals and partnering strategically with local organisations.

Establishing your humanitarian partnership strategy involves research, formal and informal interviews of your staff, partners, peer organisations, and other relevant stakeholders, and analysis of your existing resources and external humanitarian landscape.

Tips when developing a humanitarian partnership strategy:

- Conduct a desk review of existing materials about CARE’s humanitarian partnerships (see link to access Humanitarian Partnerships CARE Shares page). Collect materials on:

- Country program’s vision, areas of change, likely future directions

- Country program’s goals and objectives framework aligned with the country program humanitarian response strategy

- Lessons learned from relationships with partners

- Country program’s experiences around partnership practice, gaps and challenges

- Analyse contextual drivers and trends influencing partnership development

- Opportunities, non-traditional partnerships, government policies and priorities, civil society operating context, donor imperatives

- Map CARE and partners’ strengths and weaknesses

- Conduct a mutual mapping of strengths, weaknesses/opportunities, capacity resource needs and organisational short and long-term aspirations.

- Develop jointly a capacity strengthening plan with partners

- Analyse how you can match the technical support and training CARE can give to partners and vice versa.

[TOOL] CARE Australia Partnership Development Strategy (2011)

[SAMPLE] CARE Burundi Partnership Strategy (2013)

[SAMPLE] CARE Nepal Partnership Strategy (2015)

[SAMPLE] CARE Pakistan Civil Society Partnership Framework (2013)

[SAMPLE] CARE South Sudan Guidelines for Strengthening Partnerships (2019)

[SAMPLE] CARE Uganda Partnership Strategy (2011)

[SAMPLE] CARE Vietnam Partnership Strategy (2016)

[REPORT] ALtP South Sudan Localisation Frameowrk (2019)

Mapping and Identification of Partners

CARE is committed to working with local organisations in providing humanitarian assistance. As we aim to be a partner of choice for local organisations and networks, governments, social movements, the private sector, and other informal groups, we prioritise the mapping of local humanitarian actors in a given context to identify potential partners and determine if we are fit for each other.

A mapping exercise involves research, formal or informal interviews, and assessment of previous and existing partnerships. The results of your mapping exercise will help you identify local actors to consult and engage. This also contributes to forming relevant alliances and networks.

Things to start with when doing your mapping exercise:

- Existing and active humanitarian actors, particularly women-led and women’s rights organisations, in areas where CARE operates or will potentially operate.

- Previous partners that can potentially work with CARE again

- Local actors with strengths, expertise, and/or geographical presence complementary to CARE

- Local actors that have the same humanitarian advocacy as CARE

- Local actors that show leadership, expertise and track record in the sectors that CARE works in

- Local actors that CARE can learn from or partner with to multiply impact

- Local actors that CARE can empower to achieve shared goals

It is also advisable to include CARE in the mapping and analyse our strengths and weaknesses in each context. This will allow you to assess which potential partners CARE can be of value to and vice versa.

Criteria for Partner Identification

When identifying your partners, a set of criteria is typically developed by an inclusive decision-making committee formed within your team. Below are some criteria that you may include in your tool:

- Willingness of the local actor to work with CARE

- Composition and size of workforce

- Legal status/history

- Technical experience –

- Geographical coverage and experience

- Reputation among local civil society actors (e.g. communities, etc.) and recognition of organisation’s legitimacy by humanitarian stakeholders

- Knowledge of the local context

- Leadership, expertise and track record in the sectors that CARE works in

- Innovative and creative approaches to achieve results

- Availability of resources particularly human resources

- Access, security considerations and ability to operate in a given context or condition

- Management and governance capacity

- Mission and strategic objectives of the organisation

- Commitment to gender equality and social inclusion; protection of women, children, persons with disability, and other vulnerable sectors; value for women’s voice and leadership in emergencies.

- Capacity strengths and weaknesses

- Other specific criteria that may be required to meet the needs of the humanitarian response

Inclusive Criteria for Grassroots Organisations

Having a high score in each criterion does not necessarily mean that the partner is automatically selected. In practice, women-led and other grassroots organisations, women’s collectives, community-based groups often have less structured organisational systems. They cannot always effectively meet due diligence standards in comparison to the more established organisations.

That is why the selection committee’s deliberation of other set criteria focusing on localisation and civil society empowerment should be considered.

Organising Your Data

For continuity and evolution of your mapping exercise, it is recommended to create and maintain a database. Then, continue expanding the mapping exercise to monitor progress and update the information. Share the mapping report with all the participating actors. It is advisable to include the review of your partnership database in your quarterly or yearly country program agenda.

[TEMPLATE] Partner Mapping Database

[TEMPLATE] Partnership Directory

Partner Selection Process

A partner selection process should be objective, transparent and fair. It is also advisable to discuss the selection criteria with the potential partners and agree with them that this set of criteria also works for them. CARE and partners need to promote transparency early in the partnership development process discussing the partnership’s purpose and strategic organisational priorities. With this, each party will be able to assess the complementarity and alignment of priorities.

The main objectives of a proper selection process are:

- Identify the best matching partner. Find the balance between selecting organisations that have high capacity and demonstrated ability to influence change and deliver on shared objectives, and those who have limited capacity in the traditional sense but score high on integrity, values, and legitimacy in terms of belonging to or representing marginalised population groups, such as women grassroots organisations and social movements.

- Deliver our commitment to empowerment, accountability to impact groups and a rights-based approach. Sometimes we might find that CARE can add more value nurturing and grooming emerging civil society forms rather than capitalising on already high-performing organisations. At other times, it might be strategic to select high-capacity organisations and support their work. Partnership with smaller organisations requires more risk willingness, time, and patience on CARE’s side. Some donors give us the flexibility to work with smaller partners, others impose more stringent requirements (making donor negotiation necessary), but few would argue with the importance.

- Understand strengths and weaknesses of potential partners to inform capacity strengthening needs.

- Identify potential financial, reputational or security risks for both CARE and partners.

- Ensure a transparent process for all potential partners.

- Comply with donor and country program rules for selection of partners.

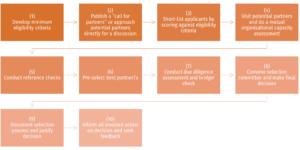

Developing Eligibility Criteria

It is important to know what you are looking for in a partner. Scoring partners against eligibility criteria will increase the objectivity of the selection process. Eligibility criteria may vary depending on the context and specific situation of your response. The following criteria are often considered:

- Proven track record in emergencies: partner has experience working in emergencies.

- Proven track record in core sectors: partner has complementary expertise in CARE’s core sectors (sectors of your response strategy).

- Geographical coverage: partner has complementary presence or connections in CARE’s target areas.

- Institutional capacity: partner has adequate policies, procedures and systems in place to support the work of the organisation.

- Finance & compliance: partner has adequate control mechanisms in place to ensure sound financial management and minimise financial risks; or has the flexibility for capacity development.

- Reputation: partner has a good reputation and is well accepted in the communities and areas of operation.

- Gender: partner is committed to work on or learn about gender equality and social inclusion.

- Shared values & principles:partner has shared beliefs, values and principles.

- Humanitarian principles:partner is independent and impartial and is guided by the humanitarian principles

- Partner diversity:the group of CARE’s partners should be a cross section of society, reflecting ethnic as well as possible partisan affiliations.

Ideally, the eligibility criteria should be agreed upon by the selection committee before publishing a call for partners.

[TEMPLATE] Partner Eligibility Criteria Rating Tool

[SAMPLE] CARE Lebanon Partner Selection Process – Pandemic Setting (2020)

Due Diligence Assessment

A mutual due diligence assessment allows CARE and the partner to have a closer look of each other’s internal structure, resources, and capacity to identify the risks that may exist when CARE and a partner are working together and to assess our common capacities to manage the relationship, implement the activities and comply with donor requirements.

Assessments should also consider ‘due diligence’ issues that might make a local organisation ineligible as a partner. While the context can call for heightened awareness, it is often possible to get enough sense on these from normal inquiries. Concerns can include:

- Political affiliation of the organisation and its key officers

- Conflict of interest due to dual role between management and executive committees

- Corruption, perhaps indicated by bad bookkeeping, audits or past donors

- Nepotism, where key staff have close family links to CARE employees, or where nepotistic hiring clearly compromises the organisation’s integrity

- Partiality to project participants such as ethnicity, religion or clan politics

- Abuse of power in the areas where we operate, including for money or sex

- Evidence of discrimination against people based on age, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, etc.

- Cases of gender-based violence, sexual harassment and exploitation linked to the organisation or any of its staff

- Unsuitable mission: for example, too much promotion of religious beliefs can be an issue

- Links to warring factions or opposing movements

- Links to terrorism

Check with your CARE Lead Member (if applicable) and relevant donors if there are any requirements related to terrorism legislation. Each CI Member / Candidate / Affiliate and their CARE Implementing Presences has procedures for screening against applicable Prohibited Party lists, such as using Bridger XL.

While the capacity assessment is focusing on existing capacities, due diligence is focusing on establishing a risk rating. Due diligence (or risk) assessments should only be conducted with pre-selected partners.

It is recommended that the due diligence assessment include program and program support staff in the selection committee to assess all relevant areas (finance, compliance, safety and security, program, etc.). This is important since some organisations who might have less experience in compliance yet are better aligned with CARE’s priorities and program objectives.

Still, through a proper and fair due diligence assessment, you will be able to define red lines and take risks specifically if partners do not meet due diligence requirements or appear to contravene humanitarian principles. Mitigating risks through capacity assessments at selection stage should be considered during this early stage of partnership identification. The results of a due diligence assessment can inform capacity strengthening activities for both CARE and the partner, and specific actions the partner or CARE might take to ensure both parties have the support they need to succeed.

Selection Committee

Decisions around partner selection are usually made by a Selection Committee (also called Partnership Committee), which oversees transparency and fairness of the selection process, and ultimately has approval authority.

The selection committee objectively reviews and verifies the partner identification and selection process. It also addresses critical challenges and contributions related to the partnership over the course of project implementation. The committee includes more than one CARE staff from the relevant funded program, program support/finance, security and partner funding agreement management units.

[TOOL] CARE Turkey Partnership Selection in Emergencies with Annexes (2022)

[SAMPLE] CARE Somalia Partnership Committee TOR with Annexes (2011)

[SAMPLE] CARE Pakistan Partnership Coordinator TOR

Establishing Non-Traditional Partnerships

CARE supports and engages with diverse partners in a variety of ways – both formal and informal. CARE values the important role of a constantly evolving civil society in mobilising citizens, holding governments accountable for the progressive realisation of human rights, and identifying new solutions to injustice for scale-up.

In our humanitarian work we recognise and reinforce the value of local actors in response – as they are often better positioned and able to provide appropriate needs-based assistance to affected populations.

To support our CARE 2030 Agenda, CARE aims to strengthen its partnerships with women-led and women’s rights organisations, informal groups, advocates and social movements that may not require financial commitments as some of them may not be formally registered. This type of partner usually contributes to information dissemination, advocacy, community mobilisation and visibility.

In some cases, CARE can support these partners through small and short-term agreements (e.g. to women grassroots networks). A specific agreement can be developed for this partnership and may not require an extensive due diligence process and deliberate eligibility criteria.

As a recommendation, try exploring other types of partnerships depending on your own programmatic goals. Ensure that we partner with a representative range of local actors. Develop a partnership strategy that includes the flexibility to accommodate non-traditional partnerships with smaller, informal organisations or social movements.

a) Assessing Mutual Organisational Capacity

Assessing our local partners’ and our own capacity is ideally done during “peace time.” It gives us enough time to manage each other’s expectations and identify areas where additional capacity strengthening might be useful.

Partners may be hesitant to assess CARE candidly due to uneven power dynamics particularly in relationships where CARE is perceived as “funder”. Therefore, we must actively counter this status quo and shift the culture to achieve honest and participatory mutual assessments.

Usually, a short visit (2-3 hours) with a partner is sufficient. This can be at our partner’s office or at CARE’s office. For remote partnership, a call or online meeting for 1-2 hours is enough if we cannot physically go to the partner’s office. An assessment may include completion of a mutual capacity assessment questionnaire, direct observation, and participatory discussion with the partner.

Conducting the Assessment

Assessments can be time consuming so keep it short. You may consider the size of the grant, duration of the program and your relationship with the partner to determine the duration and depth of the capacity assessment. The assessment may cover CARE and partners’ capacity on project implementation, rapid needs assessment, sectoral approaches, financial management, advocacy, gender programming, impact measurement, media and communications, etc.

The partner should also be able to assess CARE’s capacity for them to understand more our complementarity. It is important to note that partners may be offering capacity strengthening to CARE as well as the other way around.

As an organisation promoting gender equality and women empowerment, having gender-responsive partnerships is a priority for CARE.

As part of our assessment, you may also consider the following:

- Do CARE and partner staff reflect a balanced ratio of male and female members, especially at senior management levels?

- Does the partner adhere to the basic principles of social justice and inclusion, at the very least a commitment that all people (particularly women, girls, and other vulnerable groups) should have equal rights and opportunities?

- What experience does the partner have in working with women, girls, and other vulnerable groups?

- What experiences does the partner have in ensuring the protection and/or empowerment of women, girls, and other vulnerable groups in humanitarian or development projects?

- Do CARE and partner staff express interest and commitment to developing attitudes, knowledge, and skills to better work with women, girls, and other vulnerable groups in humanitarian response?

- Can we work with our partner to build their capacity or learn from them in gender-sensitive and gender-responsive programming?

Establishing a mutual organisational capacity strengthening and exchange plan

The term ‘capacity strengthening’ can imply that CARE always has the capacity, which is far from always being the case. Increasingly, we are collaborating with organisations with more capacity than us and we have much to learn from them.

Sometimes we have expertise that is useful to and requested by civil society actors and we can act as a direct capacity-builder. Other times, it may be through our role as a connector and broker of relations and knowledge, that we can add value.

In any case we should consider capacity strengthening as a two-way process in which we are also learning to think outside the CARE box.

Developing the Plan

The analysis of the Mutual Organisational Capacity Assessment should be done with the partners. They should also be aware of each other’s strengths and capacity building needs to develop a Mutual Capacity Strengthening & Exchange Plan. If you have many partners, it is good to have a more comprehensive analysis of all their capacities. In some cases, one partner can also provide training to another CARE partner.

The Mutual Capacity Strengthening & Exchange Plan may include the following:

- Each other’s strengths and weaknesses or capacity strengthening needs

- Availability of internal/external resources for capacity strengthening, which may include technical experts from both CARE and partners

- Capacities needed for the project

- Ideas for types of capacity strengthening activities (workshops, trainings, mentorship, webinars, staff secondment, coaching/mentoring, buddy system, etc)

- Timeline and required resources for the activities

We also need to invest in sustained and flexible funding to support capacity strengthening and diverse relationships with partners, particularly actors from the Global South. So, when developing your plan, it is advisable to include some budget and timeframe.

A key aspect contributing to the evolution of CARE’s approach to capacity building is the understanding that supporting civil society organisations to be effective development actors goes beyond what we need from partners in terms of compliance and project implementation. In other words, strengthening our partners as true actors in civil society – not only as implementers of our programs – needs to be demand-driven and included in any program design.

Capacity strengthening needs to take a long-term perspective and not only address immediate gaps. Developing capacity in human rights-based approaches, gender-responsive programming civic education, and accountability should be at the heart of our support as our partners, or social movements and activists, whom we support and collaborate with, are taking up a more active – and sometimes political roles. Resourcing capacity development is crucial, hence financial support is necessary to cover partners’ core costs and institutional strengthening.

To decide which capacity development support is appropriate, we need to use participatory approaches respecting the diversity of institutional forms and models that characterise a legitimate and vibrant civil society. We need to avoid creating “small CAREs” by imposing our organisational model on organisations for which it is not relevant.

[TEMPLATE] Mutual Capacity Strengthening Plan

[SAMPLE] CARE Philippines and Partners Capacity Development Plan (2019)

Engaging partners in Emergency Preparedness

Engaging our partners during the preparedness phase is crucial. It helps us better plan and prepare for possible scenarios. Partners are also involved in the country program’s Emergency Preparedness Planning. They should also provide inputs to the scenario-based response plans particularly if a possible area is within their area or expertise.

The country program should work on contingency agreements with local actors to significantly accelerate response time. For instance, in Indonesia, CARE’s Localisation Report shows that signing agreements with local partners at preparedness stage could accelerate response time by 14 days.

What is a contingency agreement?It is a type of investment made before an emergency occurs (anticipatory investment), it means reaching agreements with emergency response partners (local partners/operational partners and/or service providers) before our response. Usually, the agreements are non-binding and focusing on preparedness and capacity strengthening. It means a new agreement would be needed to formalise a partnership during an emergency. |

Benefits of Having Contingency Agreement with Partners

Contingency agreements improve the reliability of responses. Below are some advantages of having this in place with partners:

- Significantly extends geographic coverage

- Increases speed and implements adequate responses through existing networks of partners with strong local knowledge of the context

- Yields considerable time and financial savings

- Gives more leverage with donors having a more prepared, systematic and concrete plan

- Gives both CARE and partners better understanding of each other’s roles, responsibilities and expectations.

- Supports the long-term partnerships with local actors

Preparing with Partners

The best time to establish partnerships is outside of crises. Partnering is complex and requires time, effort, courage and vision. Getting to know another organisation (its objectives, capacities, and culture), building trust, defining the added value of the partnership, and agreeing on a joint program, can best be done over time, as part of the Emergency Preparedness Process.

Preparing together, before an emergency hits, leads to:

- More predictability of the joint response (what we aim to achieve together, who will provide what and play which role based on our respective assets and complementarities, how we will conduct joint needs assessments, what will trigger a response)

- Readiness to kick off or scale up the partnership (partnership agreement existing or pre-agreed, capacity and due diligence assessments completed, risks assessed and mitigated, procedures pre-agreed for fund transfer and programmatic/financial monitoring, pre-agreed and tested tools for response, from pre-costed project proposals to monitoring tools)

- Localised approach in preparedness

- Greater readiness of both CARE and partners to respond (key gaps pre-identified and capacity development underway, readiness to scale up, e.g. staff, funding, procuring supplies, managing heighted security)

- CARE’s enhanced readiness to respond in partnership (updated mapping of local capacities and partners, trust established with identified partners, procedures in place, staff ready and skilled to support partners, simplified compliance and monitoring tools; pre-agreed joint communications and media protocol).

Some Preparedness Measures for Partnering

Mapping

- Identifying existing or new partners to include in preparedness planning; it might be possible to identify partners in disaster-prone areas

- Updating of mapping of local organisations and their capacities

Training/Capacity Strengthening

- Offering training on emergency approaches and standards to partners (including Sphere, Gender in Emergencies, CHS/humanitarian accountability).

- Facilitating Training of Trainers (TOT) sessions for CARE and partner staff

- Conducting emergency assessment or response simulations with partners

- Providing training for support and program staff on roles, responsibilities and good practices to manage partner relationships

Partnership Agreements

- Establishing partnership contingency agreements

- Sharing CARE’s partner funding agreement templates and funding procedures in advance so partners can review and engage CARE in understanding these and tailoring them for emergencies, as needed

- Concluding contingency agreements that cover collaboration in emergencies

Accountability & Learning

- Creating space for discussions and mechanism for two-way feedback with partners/local actors to build mutually valuable and effective partnerships

- Documenting and translating standard program approaches and tools with partners

[TOOL] CARE Philippines & Partner MoU for Preparedness and Response

[REPORT] CARE Return on Investment in Emergency Preparedness (2017)

Formalizing partner funding agreements

Once the partner is selected, it is now time to formalise the partnership, agree on terms and conditions and start the project design and budgeting.

Having a contingency agreement in place developed during the EPP will significantly speed up the process. For every response or project, the following steps are recommended in close collaboration with the partner:

Contracting & Start-up Checklist

- Decide on your model of collaboration.

- Develop and agree on budget; also be transparent about CARE’s budget and resources going to other partners including core costs/SPC (within limits of confidentiality around individual salaries and the like).

- Develop and agree on mutual work plan.

- Develop and agree on M&E plan and tools.

- Negotiate terms and conditions & finalise/sign a partner funding agreement.

- Conduct inception workshop (including orientation to donor regulations)

- Transfer 1st tranche of budget to partner

Although CARE has a standard resource-based partnership agreement template, the budget and work plan should be developed jointly. Do not impose anything on the partner. Ensure that the partner funding agreement works for both CARE and partner, and that partners are sufficiently oriented on the terms and conditions of the agreement. This will prevent or lessen the frustration and problems you might encounter in the implementation stage.

Models for collaboration

A ‘model’ for partnership will describe how much, and in what ways, CARE is to be involved in operations. At one extreme, partners might have great autonomy, while CARE primarily monitors and contributes to proposal and report development. This happens in areas where there is no CARE presence, and the partners are the primary project implementer. For example, in some Pacific Island nations, CARE works with local organisations to implement the project and CARE remotely collaborates and monitors with them.

In other cases, CARE may be very hands-on in directing activities such as handling procurement, logistics or finances; providing training or mentoring; and participating in day-to-day decisions.

Ideally, CARE and partner should jointly conduct the activities, complementing each other’s capacity and filling in the gaps.

Factors that should inform decisions about the model for collaboration include:

- Capacities of each party

- Program complexity & duration

- Geographical and disaster context

- CARE and partner’s track record locally and nationally

- Amount of funds

- Ability of each party to comply with donor requirements

These factors vary case-by-case. But in general, the smaller the funding, the easier to manage by both CARE and partner. Also, the more trust CARE and partners have for each other, the more collaboration models can be explored.

[GUIDANCE] CARE Australia and HAG Remote Management in COVID-19 (2020)

[LINK] BetterEvaluation Remote Partnering Workbook (2018)

Consider these issues for collaboration

- Whether all aspects of a program can be implemented by a partner, and whether CARE should conduct some of the activities

- Which functions (e.g., procurement, logistics, warehousing, or finance) can be managed by partners, and which should be handled by CARE, taking into account relevant donor requirements

- Whether CARE should provide technical assistance or training, for example, in program approaches, standards, finance or procurement

- How the relationship will be coordinated and managed, who makes what decisions, how often management meetings take place, etc.

CI Partner Funding Agreement Policy

For CARE, a funding relationship is a type of relationship and recipients of CARE funds in all their diversity are partners. CARE International’s (CI) partner funding agreements define the contractual relationship between CARE and a recipient. CI has established a Partner Funding Agreement Policy with the intent of addressing challenges in power dynamics, equal decision-making, risk management and partner capacity strengthening.

The CI Partner Funding Agreement Policy applies when CARE is providing funding to another organisation(s). CARE and potential partners will identify and select each other through processes that are inclusive for potential partners and are in keeping with CARE’s core values and principles.

The standards and requirements in the policy ensure transparent, fair and open process throughout the CI partner funding agreement lifecycle, making the policy available to partners and enabling the partners to apply the same level of scrutiny towards CARE as CARE applies to them.

The policy provides minimum standards that all CI Members/Candidates/Affiliates and their offices must follow. This policy outlines the following management requirements during the CI partner funding agreement life cycle, which may be part of a broader partner relationship that CARE and the partner have cultivated.

Phase I – Pre-Award: Minimum eligibility requirements, partner selection, mutual due diligence and common risk assessment, capacity strengthening

Phase II – Contracting: Types of contracting mechanisms and approval thresholds

Phase III – Implementation and Monitoring: Including reporting, processing modification and amendments, periodic mutual performance and audit reviews

Phase IV – Close-out

The CI Member/ Candidate/ Affiliate and its offices must ensure the following mandatory minimum standards for its partner funding agreement management processes and procedures:

- Fit for purpose with the program needs and operational context.

- Promotion of program quality and accountability to target populations.

- Negotiating and setting out clear expectations.

- Compliant with the donor requirements and available funding.

- Appropriate support by CARE (funding, CARE program and program support staffing) to ensure management of CI partner funding agreements and demand driven capacity-strengthening of CARE staff and partners.

- Appropriate funding mechanism (i.e., type of CI partner funding agreement) for the partners to carry out and in accordance with program needs.

- Clearly describes minimum eligibility requirements as the basis for providing funds to a partner, strictly limiting additional requirements to a well-justified and necessary minimum.

- Establishes and maintains a partner selection process that ensures the respect of the principles stated in this policy.

Consider the following when developing the partner funding agreement:

- A standard format and conditions should be pre-agreed by senior country program staff (and lead member, as applicable). If possible, use established formats.

- The conditions of the agreement should be discussed and determined jointly with the partner. Do not impose conditions on them.

- Senior staff in finance, support and program departments should be consulted and approve sections of the agreement related to their area of responsibility.

- Approval and sign-off authority for agreements is defined by each CI Member/ Candidate/ Affiliate.

- Make at least one original copy of the agreement for the partner and for CARE. CARE should hold at least one original in the country program head office. The project managers must also at least get a copy for reference.

[GUIDANCE] CI Partner Funding Agreement Policy (2021)

Rapid Needs Assessment and Reporting with Partners

In most cases, CARE’s partners are the first responders when an emergency hit. That is why having a humanitarian partnership system in place will help CARE conduct rapid needs assessment, gather data and write project proposals with partners.

Orienting the partner about CARE’s rapid needs assessment and reporting protocol and tools should ideally be done during the EPP. Some country programs also conduct simulations of assessment with partners.

An emergency assessment protocol should be jointly developed with the partners. The protocol outlines the process for assessing the humanitarian situation and determining requirements for a potential response to an emergency. This process is primarily used for initial rapid assessment at the onset of emergency; additional detailed and technical assessments may be required during emergency.

In terms of reporting, some country programs have modified existing CARE sitrep template to accommodate additional data and information that the partner also intends to capture, and to merge with the template the partner is using.

Ways to Improve Emergency Assessment and Reporting with Partners

- Involve partners in decision-making when developing or rolling out protocols and tools. In most cases, the partners are more familiar with the location, local culture, political dynamics so it is necessary to have them lead the coordination process.

- Encourage the partner to present their existing emergency assessment and reporting protocols. Being able to see what the partners have been using can also help CARE improve its own tools and protocols. Or CARE and partner can both agree on complementarity.

- Give proper credit to partner for data and information. Since the partner contributes gathered data that CARE uses for its sitreps and proposals, make sure they are given full credit especially if the materials will be shared externally.

- Ensure that there is a coordination or info sharing platform accessible to all relevant staff. In some cases, CARE and partners split teams when conducting an assessment in a specific area. Having a user-friendly and accessible platform will make it easier for all staff to share real time information.

- Make sure to send the CARE sitrep to the partners. Usually, CARE processes all the data and information coming from the assessment teams and shares a sitrep to CARE International. Country programs can create a version without the confidential internal information to be shared to partners.

[TEMPLATE] CARE and Partner Joint Situation Report

[SAMPLE] CARE Philippines and Partner Emergency Assessment Protocol (2019)

Design and Implementation

After conducting the emergency assessment and gathering necessary information, CARE and partners can now jointly develop a response that will address the needs of people affected by the emergency. Involve the partners in designing the project; identifying the objectives and modes of implementation; developing a specific logic of intervention; and assigning roles and responsibilities for each party.

CARE or the partner might lead the implementation of an objective, a component or specific result in a project; or it might be that CARE and the partner have agreed on joint implementation and/or co-designed a project or program together.

Ways to Improve Project Design with Partners

- Involve the partners in proposal development. Designing a project is usually part of the proposal development phase. Make sure that you involve relevant partner staff in writing the proposal as they have more knowledge and experience in the target area.

- Analyse CARE and partner’s past experiences in responding to emergencies. If a similar response was implemented. Revisit the approaches and good practices, and brainstorm new ideas with partners.

- Consider the results of your capacity assessments with partners. These will help you identify capacity strengthening opportunities for both CARE and partners.

Developing a Work Plan

A work plan helps both CARE and partners identify key activities linked to the project’s logframe and assign roles and timeframe for each activity. This also contributes to a more efficient project implementation as both CARE and partner can track the flow of project activities and be more realistic in terms of achieving the target objectives on time.

Ways to improve work plan development with partners:

- Develop activities that reflect CARE and partner’s humanitarian values and principles.

- Be specific and agree on exact activities, division of responsibilities and timeline with partners. In the prep stage, share a standard detailed Implementation Plan with partners outlining activities and sub-activities.

- Be flexible. Particularly during emergencies, the situation will change daily. Hence the work plan may be modified multiple times to reflect the changing situation on the ground. Also, this lessens the risk that the partners carry when they do the implementation on the ground.

- Include training sessions and capacity strengthening interventions where relevant.

- Set dates for check in or updating with partners. It is important that everyone reviews the conducted activities, stays on track, and addresses immediately emerging concerns or issues. CARE must make sure that these check-ins provide those safe spaces for honest or candid feedback from partners, in the same way that we provide that to them.

- Start working on a procurement plan as soon as numbers and locations are known. Procurement may take a lot of time so the sooner this plan is ready the better.

- Develop and roll out protocols, tools and templates agreed with the partner. The tools should be user friendly and be easy to modify in an emergency setting. It’s much better if you allot a day of orientation for relevant staff. In some cases, the partner has many enumerators for monitoring, and it may take time to ensure familiarisation with new tools. So, keep that in mind when doing your work plan.

Making and Managing Budgets

Developing budget is one of the most important parts of formalising the partnership. Being able to agree on budgets for each other will contribute to having an overview of activities, identifying the mode of implementation, managing of expectations, and defining the project limitations. Ensure that you involve your partner when developing the budget for the response.

Ways to Improve Budgeting with Partners

- Agree on the budget with the partner while the proposal is being developed. Re-negotiating the budget during the implementation may challenge or affect the relationship with the partner.

- Use formats and budget line descriptions that meet donor/CARE/partner standards and requirements.

- Review budgets to ensure all costs are covered and are not too high or low. Check costs such as insurance for staff and similar expenses.

- Be clear on administration/program split.

- Pay partner overhead/core costs.

- Use established partner scales for salary, benefits, per diem and transport, within permitted donor limits. Otherwise, use common local rates.

- Avoid duplication of project staffing structure between CARE and partner. In most cases, CARE is not a direct implementer and has different responsibilities.

- Include simple narrative notes in budgets to explain costs.

- Budget line flexibility should be clear. Establish which budget lines may vary, and by how much. Budget line flexibility is usually around 10% but may vary by donor.

- Budget amendment must be governed by an approved partner funding agreement amendment / modification. Justification is essential. Discuss amendment process with partners, as CARE has been making efforts to simplify the process.

- Allot budget and time for capacity strengthening for both CARE and partner based on the capacity strengthening assessment.

- Budget for a focal person within your office (usually the partnership advisor or someone who is not the budget holder of the grant) to function as an “ombudsman” and to hear and investigate feedback and complaints in the interest of the partners.

[TEMPLATE] CARE Syria Partner Budget

Developing surge capacity with partners

Surge capacity is our ability to get the right people at the right time doing the right things to support crisis-affected communities. CARE has committed for our responses to be ‘as local as possible and as international as necessary’. Local capacity can be supplemented as required by regional and international capacity for short periods.

When responding to a crisis, we work with our local partners who also have their own emergency rosters. In some cases, partner staff are seconded to support our emergency responses or vice-versa.

Ways to build surge capacity:

- Develop an emergency roster of both CARE and partner staff. Identify their key strengths, their skills and experiences in responding to emergencies and confirm their willingness to be part of the roster in case of an emergency.

- Have capacity strengthening activities for emergency roster. Assess the current roster that you have and see how you can develop some members to improve certain skills that are needed for an emergency response. For example, if you lack an Information Manager, consider training a current member of your roster who has the closest skillset to the mentioned role.

- Consider deploying partner staff in locations outside of their areas of operation. In some cases, a staff of a local partner can be deployed and seconded to respond to an emergency.

- Develop clear agreements and guidelines on partner staff deployment. Utilising the partner staff skills should also be amendable for the staff’s mother organisation. CARE should act as a partner and should not pirate a partner staff by offering bigger compensation or better work opportunity.

[GUIDANCE] How to Develop a National Emergency Roster (2021)

Conducting Inception Workshops with Partners

An inception workshop (usually 1-2 days depending on the type of project) should be organised as soon as budgets and work plans are agreed upon. The workshop is meant to introduce the program to all relevant CARE and partner staff and kick-start implementation. Depending on the situation, this can be conducted virtually if needed.

This is the ideal venue to introduce CARE and partner’s culture and principles, explain specific donor regulations, agree on programming standards, clarify mutual expectations, refine implementation plans, understand reporting requirements, and agree upon mutual monitoring activities and responsibilities. It should also include discussion about close-out requirements so all parties can plan appropriately. The workshop will help both CARE and partner be on the same page in terms of ways of working.

Typically, staff from programs, finance, gender, procurement, communications, MEAL as well as safety & security are invited and lead short sessions. When doing an inception workshop, partners should lead some sessions for a more inclusive and participatory approach.

[REPORT] CARE Iraq Partnership Workshop (2018)

Operationalising and Sustaining Equitable Partnerships and Furthering Localisation Commitments

One of CARE’s global programming principles is that we work with others to maximise the impact of our programs, build alliances and partnerships with those who offer complementary approaches, and adopt effective programming approaches on a larger scale. We commit to working in ways that support and reinforce, not replace, existing capacities.

In addition, there is an ongoing conversation in the humanitarian sector on localisation, decolonisation and anti-racism. The recent big humanitarian crises have highlighted deep inequalities and injustices in our societies and surfaced the fact that these are also built into our organisations and structures.

This toolkit helps us confront the deeply entrenched structural inequalities, racism and power imbalances built into our ways of working as international development and humanitarian actors. Changing our approach to a more inclusive and participatory engagement with partners has become one of CARE’s top priorities.

Some inclusive practices to operationalise and sustain equitable partnerships

Program & Internal Systems

- Set clear roles and responsibilities. Be clear on the division of labor – which functions will be handled by CARE, which by partners, and what technical assistance will be provided. Define this in contracts and project documents.

- Plan ahead of time with partners. Use emergency preparedness planning as a key entry point to strengthen CARE and partners’ collective disaster response capacity.

- Budget adequately. Overhead and staffing costs are very real issues for CARE and the partner and this can hinder a fair partnership agreement. While partners are doing the bulk of the implementation, CARE often has not allowed partners to adequately cover their operational costs. Investing in the partners staffing structure and overhead/core costs is a critical success factor for any response and key for a successful partnership.

- Involve partners in all phases of the project cycle. Partners should be involved in the response strategy, needs assessments, program design and proposal development to avoid misunderstanding and increase ownership.

- Accept and manage risk and imperfection. Partnerships can be marred by risk aversion and perfectionism. Intense questioning of details can delay contracts, disbursement, program design and implementation.

- Make sure support systems are responsive to partnership. Heavy paperwork and reporting are not conducive to rapid emergency work; even less so when engaging and working with partners. Simplify procedures where necessary and keep things light for our partners where possible thus still meeting donor’s and auditor’s requirements.

Collaboration & Communication

- Designate a collaboration-oriented partnership focal point. One locally-based program staff member should be the focal point for all dealings with a partner. Support and finance staff should also be placed in the area of implementation for assistance with the work. Designate a local staff with technical ability, good attitude, and strong communication and negotiation skills. Ensure that they are mandated to take decisions, as well as to consult and inform senior managers.

- Consult and be transparent. Decision-making should be as transparent as possible between CARE and partners, including on budget and finances. It is also important to share information and seek input on decisions but without over-consulting.

- Have good internal coordination. Confusion on roles and authorities can lead to too many people getting involved in internal decisions and procedures, causing delays and mixed messages. Be clear who must be consulted and who signs off on what. Use a management model where a locally-based team, fairly representing both CARE and partners, coordinates routine matters, and a senior management team meets to resolve policies and issues.

Relationship

- Ensure the value addition for both parties is clear. A clear decision-making process on whether and who to partner with will examine and clarify what value the partnership brings to both parties.

- Share power. We recognise that CARE and partners have equal yet complementary strengths, a dynamic that must be reflected in leadership and decision-making. The support or management that CARE provides must be mutually agreed upon with local partners.

- Act as equals. Local partners often complain of being treated as servants by INGOs. CARE by virtue of organisational capacity may take on the role of resource mobiliser, donor manager, and/or technical expert, but we must understand and acknowledge that these roles are only part of what makes a project effective. Partners provide indispensable value to the project with their own skills and experience, indigenous knowledge, and established relationships with local government and community stakeholders. CARE’s attitudes must reflect equality.

- Accept and manage different roles and tasks. Working in partnership requires a different skill set among CARE staff. Moving away from that of direct implementer, the role for CARE staff will focus more on building relationships, monitoring, capacity strengthening and contract management.

- Invest in building interpersonal relationships. People need to trust and respect each other if they want to establish a fruitful relationship. The representatives of organisations are individuals, and therefore interpersonal relationships are central to a successful partnership between organisations.

Learning & Ways Forward

- Learn from partners. Partners have rich knowledge and expertise about the operational context we are working in, that CARE does not always tap into. CARE should engage in strategic and programmatic discussions with partners, discuss developments and scenarios of the context, and engage in joint preparedness as well as strategic planning processes. There is a lot more we can learn from our partners that can enhance the quality and effectiveness of our response.

- Prepare and nurture partnerships outside of emergencies. Pre-emergency is the prime time to invest in partnership. It is difficult to establish trust and build relationships during the height of an emergency when the focus must be on saving lives and alleviating suffering. Ideally, CARE will develop partnership relationships during times of non-emergency. Long term investments in capacity strengthening will enhance the quality and effectiveness of response. It is important to have access to committed and consistent funding for capacity strengthening for partners (or for CARE from partners) in topics including security management, financial management, humanitarian standards, emergency preparedness and gender in emergencies.

- Advocate with donors regarding budget amendments or flexibility. Since CARE is in direct contact with the donors, make efforts to negotiate with donors on certain budget concerns especially if these affect partners.

- Continue to be a thought leader with partners. Proactively engage partners in local, national, or international dialogues on localisation. Intentionally bring partners to the table to influence change at local and global levels. Where possible, provide the support that they need to meaningfully participate in these spaces.

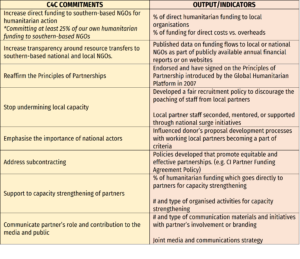

- Measure and report progress towards delivering on our commitments (including 25% of our humanitarian funding to local actors and communicating our partners’ contributions to the media and public).

- Seek new and flexible funding. Strategically redirect new or existing resources to support localised responses, including partners from the Global South. For example, use or seek development or unrestricted funding that supports partners’ institutional development, especially for emergency preparedness and pre-crisis.

Common Mistakes in Partnerships:

- Creating inflated expectations.

- What to do? Discuss expectations with partners from the start. It can be dangerous if a partner sees a simple partnership contingency agreement or Memorandum of Understanding as something more than it is, or if promises to strengthen capacity are not delivered. It is good to have realistic visions for relationships.

- Delaying payments and deliverables.

- What to do? Ensure that the Country Program’s financial and administrative systems are flexible enough to allow for real-time transaction of funds, resources, and other support as required by the partner, to set them up for success.

- Overfunding or overstretching the partner

- What to do? It is important to have a clear sense of other projects and overall capacity of the partner to carry out the agreed upon work. Good partners are likely working with other NGOs and an effective balance needs to be maintained.

[GUIDANCE] CARE International Civil Society Resource (2016)

[GUIDANCE] ALtP Consortium – Partnership Practices for Localisation (2019)

[TOOL] Partnership Enhancement

Communications and Media Relations

Communications work plays a vital role in raising awareness of an ongoing emergency. Working with partners helps CARE amplify messages to our target audience and support fundraising and resource mobilisation activities.

It is important to have a clear understanding of media protocols, sign-off procedures, and visibility requirements during the partnership. A partnership may provide some confusion and frustration on this at times. Both partners want to be recognised for their work. But a partnership also provides an opportunity to complement each other’s communications and media efforts.

Ways to Improve Communications Work with Partners during Emergencies

- Involve the partners in developing a communication plan or strategy. Ensure media and communications are in your Emergency Preparedness Plan.

- Agree on how visibility of CARE and the partner will be handled in printed and online materials, accessories, activity branding, etc. Before conducting an emergency relief distribution, make sure to include CARE and partner’s logo (as well as donor logo if applies). This will send a message to the public that CARE and partners are already on the ground responding to the needs of the affected people. Also, have the same size of all logos in communication materials.

- Identify you partner spokespeople. This will likely be the Executive Director and Emergency Coordinator. Ensure they have undergone media training.

- Identify a media focal point of partner/s. The person will work closely with CARE in handling media requests or gathering photos/videos.

- Keep partners informed on communications strategy and activities. This ensures that all communications activities are well coordinated with partners especially if there are media visits, interviews and documentation that need partners’ participation.

- Train partners on how to deal with the media, particularly on interviews with international media. Ensure the partner knows what to do if they are approached by a journalist. Monitor national news for information relevant to CARE and partner’s work.

- Ask partners to share communication material (photos, videos) from the areas of implementation. Give the proper credit to them when sharing the materials internally and externally.

- Assist partners to develop profiles or communication materials as needed.

[SAMPLE] CARE Philippines HPP Media and Communications Protocol (2019)

Monitoring & Evaluation

Monitoring and evaluation (M&E) help in understanding how the assistance and support that CARE and partners provide to disaster-affected communities. It is therefore a critical part of CARE’s Humanitarian Accountability Framework (HAF). CARE recognises that crises impact women, men, and vulnerable groups (children, persons with disability, elderly, indigenous peoples, persons of diverse gender identity and sexual orientation) differently. To ensure we do no harm and provide quality, gender-responsive and life-saving assistance, our MEAL systems with partners must reflect this basic gender in emergencies principle.

While monitoring aims to ensure that activities meet the project goals and funds are used in compliance with partner funding agreements, it is not meant to be an exercise in ‘policing’ partners. In fact, CARE should promote mutual monitoring of performance by CARE and partner staff. Instead, it is an opportunity for both to learn and improve. Partners often welcome this approach, and some even ask CARE to monitor more, to better understand their challenges.

Ways to Improve Mutual Monitoring and Evaluation with Partners

- Develop an M&E plan, including clear and simple formats at the start of the project to ensure that CARE and partner are aware of the M&E standards and roles of each other. Agree on key indicators, data tracking sheets and reporting requirements. Agree on modes of monitoring and level of engagement.

- Use simple and user-friendly tools. Focus on getting essential data only including sex, age and disability-disaggregated data. Complicated tools and heavy protocols are not suitable for emergencies. Overburdening the partner with paperwork and too many data to gather can cause delays in program implementation.

- Share data protection guidelines and mechanisms for launching formal complaints. These may differ per country or context, so it’s best to check what is most updated in your area.

- Provide M&E capacity strengthening activities for both CARE and partner staff.

- Periodically evaluate the performance of both CARE and partner(s) towards the achievement of intended outputs/outcomes and the respect of commitments in terms of partnership.

- Develop a feedback and accountability mechanism with partners that covers feedback from project participants, stakeholders, CARE and partner staff. Also, ask proactively for feedback and solutions to challenges. Partners often have great ideas on how to improve programming.

- If the context does not allow for local visits (e.g. Syria, Afghanistan, and Somalia), use third-party monitoring or contract external consultants. Video live-streaming or social media can provide another solution to keep in touch with partners in remote areas.

- For remote monitoring, maximise the use of online communication platforms. Be strategic in using online media and make sure that the partner also has the same resources such as proper equipment and Internet connectivity. Also, be mindful of not draining partners with too many calls and online appointments.

[TEMPLATE] Partner Monitoring Plan Status Report

[TEMPLATE] CARE Somalia Partner Monitoring Tracker

[LINK] CARE’s Collaborative Approach to Remote Monitoring (2015)

Monitoring the Partnership

Monitoring the partnership itself is as important as monitoring program activities. If there are challenges in partnering together, this should be identified and addressed. If issues between the parties are not addressed adequately, this may become an obstacle for responding effectively during an emergency.

Continuous monitoring of the partnership relationship therefore is critical. CARE should be open to receiving feedback and complaints from partners and a systematic process needs to be in place to facilitate this and track performance. Some recommendations that could help to monitor and evaluate the partnership itself include:

- Make time during face-to-face program meetings with the partner to discuss the partner cooperation and ways to improve this.

- Appoint one focal person within your office (usually the partnership advisor or someone who is not the budget holder of the grant) to function as an “ombudsman” and who hears and investigates feedback and complaints in the interest of the partners.

- Conduct a partnership review/survey (during implementation and after close-out) to understand better and act upon feedback from the partners.

[SAMPLE] CARE Denmark Partnership Survey

[TEMPLATE] Partnerships Management Tracker

[TOOL] Key Dimensions of Partnership Effectiveness and Localisation

[TEMPLATE] CARE Jordan Partnership Scorecard – Quarterly Check-in

Strengthening CARE’s Accountability with Partners

Being accountable to our partners means that we have a shared commitment to achieving our goals together, ensuring each other’s safety and learning from our experiences and expertise. We acknowledge that both CARE and partners have responsibilities and accept these for our actions and their implications.

Factors that Contribute to Strong Accountability

- Communication, openness, and information-sharing: Good communication is at the heart of successful partnerships and should be taken very seriously. It can make or break the partnership. Communication challenges are often amplified in remote partnerships.

- Equity, respect and mutual accountability: Equity in partnerships is critical and involves being valued for what each party brings, enjoying equitable rights and responsibilities, having a say in decisions, benefiting equitably from the partnership, creating mutually-beneficial value. Equity is built by truly respecting the views, attributes, and contributions of all those involved.

- Shared capacity, organisational development & learning: Competitiveness can easily break a partnership. Agreeing to explore and build on the added value of collaboration and understanding the right of all partners to gain from their engagement in the partnership is an important starting point to build commitment to the joint initiative. An effective partnership should deliver mutual benefit.

- Shared vision, mission, and goals to achieve better impact:Partnerships are often marked by real (or perceived) anxieties about working with organisations that are different from us. A commitment to exploring each other’s motivation, values and underlying interests will build understanding and appreciation of the added value that comes from diversity, quelling fears that differences may lead to conflict or relationship breakdown.

- Existence of mutual monitoring and evaluation mechanisms for efficient feedback and participation:While it is common to assess the outcomes of the joint initiative, assessing the health of the partnership to deliver on these outcomes is as critical. This can also provide key information on the effectiveness of the partnership and its value-add, and generate lessons learned on good partnering.

[TOOL] CARE Accountability in Partnerships Learning Questions (2017)

Supporting Partners for Increased Voice with Donors, Humanitarian Stakeholders and Media

When requested by our partners, and when the context allows it, we should be willing to step up and stand side-by-side with partners to advocate and raise awareness of certain issues. Advocating with partners will help us position our stand and add value to continuing discussions on topics we care about.

CARE should analyse and use the possibilities to lobby with governments in the Global North (e.g. at EU level) using its international network within and outside of CARE, in coalition with peers and other civil society actors.

Also, during emergencies, many humanitarian cluster meetings take place to discuss identified humanitarian needs and gaps. This type of engagement is a good way for both CARE and partner to advocate, speak up and share.

CARE can be a convener of meeting spaces where we can bring our local partners, individual advocates or ambassadors we work with and volunteers. Sometimes, it is also more effective to hold informal spaces that are particularly important in contexts where formal spaces do not exist or where the existing spaces are unsafe, not inclusive to grassroots organisations (especially women’s rights organisations, as well as trade unions) or not efficient. Where spaces cannot be created locally, facilitating access to regional platforms can be an alternative. Our role is to

CARE can be a convener of meeting spaces where we can bring our local partners, individual advocates or ambassadors we work with and volunteers. Sometimes, it is also more effective to hold informal spaces that are particularly important in contexts where formal spaces do not exist or where the existing spaces are unsafe, not inclusive to grassroots organisations (especially women’s rights organisations, as well as trade unions) or not efficient. Where spaces cannot be created locally, facilitating access to regional platforms can be an alternative. Our role is to “enable effective and inclusive relations and negotiation between concerned actors”.

Advocating with Donors about Partners’ Role

As one of our global commitments to the Charter for Change, we emphasise the importance of local and national actors to humanitarian donors. We advocate to donors to make working through national actors part of their criteria for assessing framework partners and calls for project proposals, and to increase local actors’ direct access to funding. To support this advocacy, CARE needs to invest in strengthening evidence-based documentation and research showcasing the added value and role of local actors in humanitarian response.

Closing Out

Closing out a partner funding agreement is a phased process. Identify at the inception stage the key activities to ensure there will be a smooth close-out. Closing out a partner funding agreement is not the same as closing out the collaboration. If the cooperation was mutually satisfactory, the partnership can continue through a contingency agreement (non-project based), or by starting a new partner funding agreement for another project.

Ways to Effectively Close a Partner Funding Agreement with Partner

- At least 30 days prior to the end of the partner funding agreement, conduct a close-out meeting with the partner to plan close-out activities

- Verify all project activities have been completed

- Review and approve final financial and narrative reports in accordance with donor requirements

- Conduct partnership survey evaluation

- Invite partner to co-facilitate the After Action Review (AAR)

- Recognise and celebrate achievements of the project

- Send close-out letter to partner, project participants and involved stakeholders

- Transfer remaining funds/balance if owed to the partner for eligible costs

- Consider donating project assets to partner (refer to donor guidelines if permissible and procedures)

- Archive final records and project documents

- Consider new project with the same partner

To efficiently advocate for localisation, we need to demonstrate the effectiveness of our partnerships and relationships with local partners. It does not just promote and enhance localisation but strengthens organisational capacities of CARE and our partners. Setting partnership output/outcomes will help improve our humanitarian action and achieve our program objectives.

Assessing partnership quality and effectiveness

A great humanitarian partnership is only possible if all parties collaborate equitably with each other, specifically in a crisis setting where things change quickly.

There are cases when CARE or the partner has limited knowledge or capacity to implement best practices for activities like distribution, and a weak grasp of issues like SPHERE standards, accountability mechanisms and gender sensitive programming. Therefore, it is important to assess the quality and effectiveness of partnership so both CARE and partners can learn from the experience and be able to address identified challenges or replicate best practices.

Learning questions to assess partnership quality and effectiveness

On Results and Impact

- What results does the partnership produce? Are there clear and measurable partnership output/outcomes?

- Do CARE and partners achieve their shared goals (joint project) and organisational goals?

- How does the partnership add value to each organisation?

- Does the partnership achieve wider impact and influence?

On Functions and Efficiency

- Are there strong and appropriate communications and accountability mechanisms in place?

- Are there enabling internal processes and systems of CARE and partners for partnering? Are there flexible processes/systems and light bureaucracy for partner compliance?

- Do CARE and partners maximise the strengths and expertise of each other during the partnership?

- Are the roles and responsibilities of each other clear? Are they outlined in some forms of agreement such as MOUs?

- Are there regular reviews to assess the quality of partnerships and address emerging issues and concerns?

On Collaboration

- How does the partnership promote collaborative approach?

- How are partners provided opportunities to speak up and advocate at the discussion and decision-making tables?

- Does the partnership present joint branding and visibility?

- Are individual expertise and preferred ways of working incorporated consciously and constructively in your partnerships or response strategy?

- How do you allot time and resources to strengthen capacities of each other and to building/maintaining the partnership?

- Does the partnership display willingness of all parties to share risks or take measured risk for the benefit of the partnership?

Tips to strengthen the partnership and ensure program quality

- Foster common understanding on a program by holding an inception meeting for CARE and partner staff to discuss standards, the objectives, activities, obstacles, program management, etc.

- Run training sessions for partner staff at the earliest possible time. Ensure that they are relevant, concise, and well targeted, and try to conduct them where program activities are being implemented.

- Provide tools and materials to support training. Preparing translated manuals prior to an emergency is a good practice.

- Follow up on training with physical visits, meetings, or refresher courses. This will be much more effective than just one-off events.

- Consider seconding CARE staff to partners to mentor them for a defined period or arrange for partner staff to learn more about our operations.

- Ensure that program monitoring covers quality and standards issues.

- Budget for partner capacity strengthening interventions in project proposals.

- Give partners access to tools and materials such as the CARE Emergency Toolkit, the Gender Marker, etc.

[REPORT] CARE Lebanon Partnership Workshop (2020)

[REPORT] Localisation in Practice: A Pacific Case Study (2016)

Strengthening evidence-based Documentation and Learning

CARE should continuously strive to be a learning organisation, demonstrating openness and transparency by sharing our best knowledge and methods and constantly seeking to learn from others.

CARE has access to a wealth of expertise, good practices, and innovation from within the CARE family and from our networks and partners. Our role should consist in collecting, documenting, and sharing approaches, and adapting and contextualising knowledge and well-tested models to make them useful to local partners and thereby scale up gender-responsive approaches.

Tips to strengthen documentation and learning with partners

- Jointly develop a documentation and learning plan with partners.

- Identify information and existing models that can be adopted to avoid duplication of resources.

- Allot budget for documentation and learning activities.

- Set up a simple yet efficient information/knowledge management system with partners.

- Invest in equipment for documentation like digital cameras and audio recorders.

- Conduct monthly or quarterly learning reviews and knowledge exchange with partners – can be done physically or virtually.

- Organise activities that bring together civil society actors, researchers, INGOs, multilateral organisations, donors, government officials and other relevant stakeholders on specific agendas. Create an opportunity for all to learn from each other and together.

- Synthesise findings from monitoring visits and share with the entire team.

- Develop learning materials such as human-interest stories, case studies, brochures etc.

Shifts in Power Dynamics and Leadership

The shifting of power relations in favor of formerly excluded groups (including women) can evoke resistance of those in power and lead to backlash against these groups. To avoid doing harm, CARE should expand and strengthen spaces for dialogue and negotiation, in order to channel demands and negotiate competing interests between actors within civil society, or between civil society, state actors (including political parties) and private sector.

In fragile contexts, characterised by mistrust at all levels and between civil society and the state, CARE should play a role in improving trust and re-building social contracts within civil society and between CSOs and the state through dialogue and accountability mechanisms aimed at improving governance and service delivery.

As an international non-partisan organisation, CARE should sometimes play a mediator role, and help parties to identify solutions that will enable them to move forward. This role can also involve training local conflict mediators and supporting mediator organisations.

CARE is privileged to have access to millions of women and to a range of women’s organisations and networks who play such conflict mediator roles on a daily basis, and from whom we have much to learn. As part of the context analysis and do-no-harm approach, CARE can partner with and train local actors in conflict mapping and gender analysis tools to map relations among stakeholders, both between civil society organisations and between civil society and other stakeholders.

Fit-for-partnering Review Guidelines

A Rapid Accountability Review (RAR) is a rapid performance assessment of emergency response against CARE’s HAF that takes place within the first few months of an emergency response. It generates findings and recommendations that are used to make immediate adjustments to the response. It is also a key source for any response review and performance management process. It usually entails interviews with CARE management, staff, communities and other key external stakeholders, and is led by an independent team leader. The overall goal of the RAR is to improve the quality of CARE’s response by assessing its compliance with established good practice.